Most people have skin lesions such as moles, and most are harmless. The challenge is that melanoma, the most dangerous type of skin cancer, can look very similar to benign lesions, especially early on. That is why dermatology relies on careful visual inspection and dermoscopy, and why early detection matters. In recent years, AI has moved from research into routine decision support, helping clinicians triage lesions and prioritize suspicious cases, but these systems can also fail in ways that disproportionately affect marginalized patients without being obvious to users.

The same deep neural networks that drive strong performance also make bias harder to spot. Traditional melanoma risk models might use a small set of variables like age, sex, and a few lesion descriptors, while neural networks learn directly from high-resolution images and can pick up subtle visual cues. The trade-off is transparency: with a handful of inputs, you can usually explain what drives a prediction, but with millions of learned parameters, you often cannot. That makes it easier for models to rely on shortcuts in the data, and for uneven performance across groups to stay hidden unless you measure it directly.

AI Fairness

Thankfully, detecting and mitigating the biases of deep neural networks is an active field of research that falls under AI Fairness. AI fairness is the goal that an AI system’s performance and impact do not systematically disadvantage certain groups of people compared with others. It is a multidisciplinary field shaped by voices from machine learning, medicine, ethics, law, social science, and the communities affected by these systems.

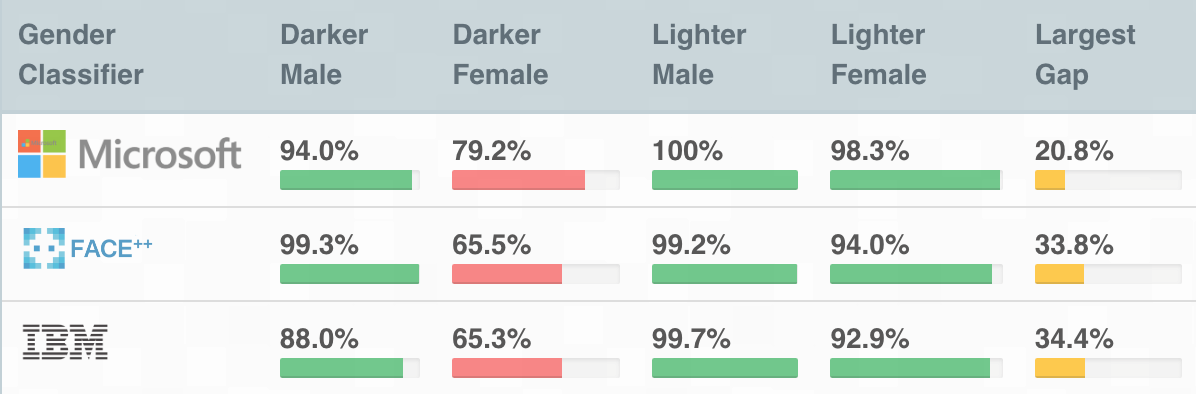

One of the early, widely cited fairness wake-up calls in computer vision was the 2018 Gender Shades audit by Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, which tested commercial face-based “gender classification” systems and found large error gaps across skin tone and gender presentation: darker-skinned women were misclassified far more often (up to 34.7% error), while lighter-skinned men saw much lower error (up to 0.8%).

One important concept in detecting bias highlighted by Gebru and Buolamwini is intersectionality: problems can appear only when you look at combinations of traits, not each trait on its own. A system might look acceptable when you average results across all women, or across all darker-skinned people, yet fail badly for darker-skinned women. In practice, this means fairness checks should break results down into combined subgroups where possible; otherwise, the biggest gaps can stay hidden in the averages.

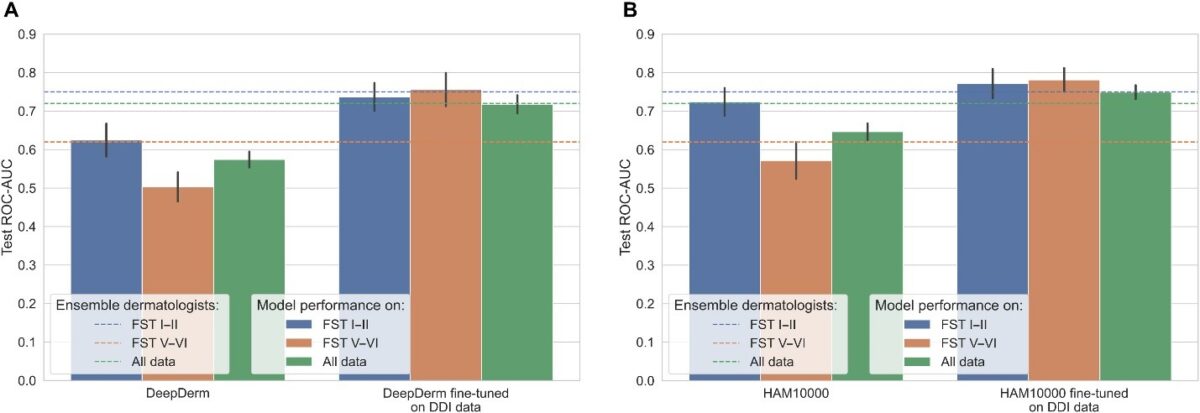

The impact of Gender Shades led to similar studies in dermatology: when researchers stratified model results by skin tone, they sometimes saw drops in sensitivity for darker skin. In other words, the models were missing malignant lesions in people with brown and black skin. Unavoidably, if the data does not represent the full range of real patients and real images, the model’s benefits won’t be distributed evenly.

Why Are Dermatological AI Systems Biased?

One reason the bias in dermatological AI systems happens is simply what the model sees during training. A lot of dermatology AI is built on large, public datasets that were collected among mostly Western, lighter-skinned patient populations. If darker skin tones, certain conditions, or certain image styles are rare in the training data, the model has fewer chances to learn reliable patterns for them. In practice, that can show up as lower accuracy for some groups, even though the overall accuracy is high.

Even if you rebalance the dataset, gaps can persist because models are usually built and tuned to do well on specific benchmarks. That introduces a kind of algorithmic bias: design choices, preprocessing steps, and hyperparameter tuning are optimized for what the benchmark rewards and what the benchmark looks like.

On top of that, the images themselves can differ in systematic ways. Many pipelines are implicitly tuned to lighter skin, from color normalization and contrast assumptions to artifact handling. Here are two examples of this:

- Dermatoscopic images contain hairs, which often need to be removed before melanoma detection. Many hair removal pipelines assume that hair must be darker than the skin, as it is on light-skinned patients. This assumption does not hold for many dark-skinned patients, especially with gray hair, and would result in failures.

- Similarly, some melanoma pipelines assume the lesion is darker than normal skin, but lesions can be lighter due to depigmentation; this contrast is often much more pronounced on darker skin and can push a model toward the wrong prediction.

The takeaway is that a single “overall accuracy” number can hide these uneven failure modes. If data, benchmark tuning, and preprocessing assumptions can all skew performance, the only way to know is to measure it directly. That’s where fairness evaluation comes in: you report performance by relevant subgroups and check whether errors and confidence stay consistent across them.

Evaluating AI Fairness in Dermatology

Evaluating the fairness of dermatological systems often involves complex statistical methodologies because we don’t have access to skin color information. Instead, we try to infer skin color from photographs of the patient. That starts with choosing a way to quantify skin tone, and one common approach in dermatology is the Fitzpatrick scale, which classifies skin types from I to VI based on typical reaction to sun exposure: I burns very easily and rarely tans, while VI rarely burns and is deeply pigmented.

However, even the way we measure skin tone can introduce bias. The Fitzpatrick scale effectively gives more resolution to lighter and medium skin (types I–IV) than to darker skin (types V–VI). It is also subjective, and its categories do not capture the full range of pigmentation and undertones people have. That is why many fairness studies are moving toward alternatives. The Monk Skin Tone scale is a 10-shade, open tool created specifically for image-based labeling, with finer gradations across the spectrum.

At FERIT’s Research Group for Computer Science and Human-Computer Interaction, one of our focus areas is estimating skin tone directly from dermatoscopic images. This skin tone signal can then be used to stratify model results and check whether dermatology AI performs unevenly across groups.

In one line of work, we benchmarked several skin tone estimation methods on synthetic images where the “true” skin tone is known, and found that simple color-clustering approaches can be surprisingly robust. We then used this approach to audit skin-lesion segmentation models and saw a consistent pattern: performance was highest on lighter skin, and the gap was difficult to close without more balanced, publicly available datasets.

What Can We Do to Fix This?

As researchers, engineers, clinicians, and patients, we can all play a role in making these models more equitable. The first and most important step is better data: larger, well-documented datasets that reflect real patient diversity across skin tones, conditions, devices, and care settings. From there, fairness has to be treated as part of routine evaluation, not a one-off audit, with subgroup reporting, external validation, and monitoring after deployment so performance gaps are found early and addressed rather than averaged away.

Bias in AI can be insidious, and clinicians are often unaware it exists, especially when it comes from commercial systems that have little incentive to disclose where they fall short. That makes awareness a practical part of the solution: the more everyone in the chain understands how and why these gaps appear, the more likely they are to ask the right questions, demand subgroup evidence, and spot problems early. Articles like this one are one small way to help shift fairness from a niche research topic into a routine expectation.

There are also technical approaches that try to reduce bias at the model level, even when you cannot immediately fix the dataset. Usually, these approaches try to “hide“ parts of the image or internal model representations that contain information about the skin color. This forces the model to ignore skin color information during training. However, while these approaches can improve performance, they rarely make fairness “automatic” or permanent. If the training data is skewed or the deployment setting shifts, the model can still pick up new shortcuts, so you still need representative datasets and subgroup evaluation as a backstop.

Conclusion

Dermatology is a natural fit for AI because so much of the work is visual, but that also makes it easy for models to inherit and amplify the biases embedded in images and datasets. The practical takeaway is simple: trust should be earned with evidence, not implied by a single accuracy number.

As a patient, it is worth being curious about whether AI is being used in your care, what it is used for, and what its limitations are, especially if a tool influences triage or follow-up decisions. As a clinician, healthy skepticism is part of responsible adoption: ask for subgroup performance, external validation, and clarity on when the model should not be used. And for AI researchers, fairness should be treated as a first-class evaluation target, with routine subgroup reporting and calibration checks, rather than an optional add-on after the model already looks good on average.

References

- Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification. Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (FAccT), PMLR 81, 77–91. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html

- Tjiu, J.-W., & Lu, C.-F. (2025). Equity and Generalizability of Artificial Intelligence for Skin-Lesion Diagnosis Using Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Smartphone Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina, 61(12), 2186. https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/61/12/2186

- Benčević, M., Šojo, R., & Galić, I. (2025). Skin Color Measurement from Dermatoscopic Images: An Evaluation on a Synthetic Dataset. Proceedings of the 67th International Symposium ELMAR 2025. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/11194005

- Benčević, M., Habijan, M., Galić, I., Babin, D., & Pižurica, A. (2024). Understanding skin color bias in deep learning-based skin lesion segmentation. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 245, 108044. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169260724000403

- Schumann, C., Olanubi, G. O., Wright, A., Monk Jr., E., Heldreth, C., & Ricco, S. (2023; revised 2024). Consensus and Subjectivity of Skin Tone Annotation for ML Fairness. arXiv:2305.09073. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.09073

- Alvi, M., Zisserman, A., & Nellaker, C. (2018). Turning a Blind Eye: Explicit Removal of Biases and Variation from Deep Neural Network Embeddings. arXiv:1809.02169. https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.02169

Author

dr. sc. Marin Benčević

Text is partially generated by artificial intelligence